A few months ago I attended the lecture-performance "Dancing and the Brain" at Nationale Opera and Ballet in Amsterdam. I thought it was really cool to discuss how dancing affects our brain, and join lecture with dance demonstrations. Inspired by the lecture, here is my version of dancing and the brain, with an emphasis on ballet, the form of dance with which I have most personal experience.

To understand how dancing affects the brain, we need to start with discussing what dancing really is in general, and then how ballet differs from that. In general, dancing can be defined as a combination of movement, often with music, often in the service of artistic expression and conveying a certain aesthetic experience (but sometimes also a social action). As such, dancing inevitably is a training of motor coordination, which is requires coordination between many brain areas, including the parietal and premotor cortex (Cross et al., 2009). Each type of dance has a specific movement vocabulary, and when dancers watch their "own" type of dance, their ventral premotor cortex gets more active than when they watch other forms of dance (Pilgramm et al., 2010). This suggests that dancing helps to set up specific motor programs (for example, in ballet dancers it has been shown that the area of motor cortex associated with the foot has increased; Meier et al., 2016). Dance has also been shown to be associated with more sensitivity in the recognition of other's movements (Sevdalis & Keller, 2009).

Now let's move on to the specific form of dance that is ballet. What is unique about ballet is that it consists of a very specific movement vocabulary that has changed little over the centuries. A strong emphasis is placed on the lines created by poses and movements. As such, I would expect that this is associated by a very strong sensitivity to small differences in the production and perceptions of these patterns of movement. A lot of this sensitivity is visual because ballet dancers perfect their movements largely with the help of mirrors. This is probably different in many other forms of dance that do not rely so strongly on mirrors. Moreover, because ballet involves the precise repetition of a relatively fixed movement vocabulary, this is associated with increased ability to memorize movement sequences (Smyth & Pendleton, 1994). This often happens by chunking a series of movements into bite-size pieces, which ballet dancers have been shown to be relatively good at Foley et al. 1991 . I am very curious whether this also transfer to better memory in general. I would not be surprised if ballet were a good training method for memory and cognitive control (see also van Vugt (2014) for similar ideas).

Apart from training memory and cognitive control, ballet is likely to be also excellent training for your attention. When you are in the studio, you need to focus on many pieces of information at the same time: the series of movements you are supposed to produce, the muscles you are supposed to be tensing and relaxing (while dancers have been training for years to automatize those patterns, they keep honing them every single day of their careers).

Apart from those technical aspects, ballet is most importantly an art, so the best part for a dancer usually comes when they can forget about the steps and totally inhabit the character or the mood that comes with the dance. They then typically forget everything around them and enter something like a flow state. I would not be surprised if ballet dancers are very good at imagination, but I have not found any studies that test that. I would predict this would lead to a strengthening of a set of brain areas called the default mode network, involving the posterior cingular cortex, medial prefrontal cortex and medial temporal lobe, which are all involved in creating stories in your mind, and disconnecting from outside distraction. While there have been

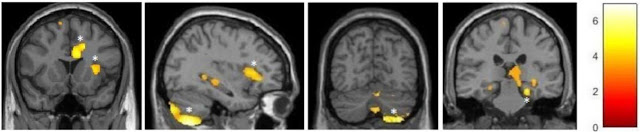

|

| Cortical representations of hand and foot in Meier et al (2016) |

To understand how dancing affects the brain, we need to start with discussing what dancing really is in general, and then how ballet differs from that. In general, dancing can be defined as a combination of movement, often with music, often in the service of artistic expression and conveying a certain aesthetic experience (but sometimes also a social action). As such, dancing inevitably is a training of motor coordination, which is requires coordination between many brain areas, including the parietal and premotor cortex (Cross et al., 2009). Each type of dance has a specific movement vocabulary, and when dancers watch their "own" type of dance, their ventral premotor cortex gets more active than when they watch other forms of dance (Pilgramm et al., 2010). This suggests that dancing helps to set up specific motor programs (for example, in ballet dancers it has been shown that the area of motor cortex associated with the foot has increased; Meier et al., 2016). Dance has also been shown to be associated with more sensitivity in the recognition of other's movements (Sevdalis & Keller, 2009).

|

| In my home office |

Now let's move on to the specific form of dance that is ballet. What is unique about ballet is that it consists of a very specific movement vocabulary that has changed little over the centuries. A strong emphasis is placed on the lines created by poses and movements. As such, I would expect that this is associated by a very strong sensitivity to small differences in the production and perceptions of these patterns of movement. A lot of this sensitivity is visual because ballet dancers perfect their movements largely with the help of mirrors. This is probably different in many other forms of dance that do not rely so strongly on mirrors. Moreover, because ballet involves the precise repetition of a relatively fixed movement vocabulary, this is associated with increased ability to memorize movement sequences (Smyth & Pendleton, 1994). This often happens by chunking a series of movements into bite-size pieces, which ballet dancers have been shown to be relatively good at Foley et al. 1991 . I am very curious whether this also transfer to better memory in general. I would not be surprised if ballet were a good training method for memory and cognitive control (see also van Vugt (2014) for similar ideas).

Apart from training memory and cognitive control, ballet is likely to be also excellent training for your attention. When you are in the studio, you need to focus on many pieces of information at the same time: the series of movements you are supposed to produce, the muscles you are supposed to be tensing and relaxing (while dancers have been training for years to automatize those patterns, they keep honing them every single day of their careers).

|

| During an EEG experiment at the Night of Arts & Sciences, 2019 |

Apart from those technical aspects, ballet is most importantly an art, so the best part for a dancer usually comes when they can forget about the steps and totally inhabit the character or the mood that comes with the dance. They then typically forget everything around them and enter something like a flow state. I would not be surprised if ballet dancers are very good at imagination, but I have not found any studies that test that. I would predict this would lead to a strengthening of a set of brain areas called the default mode network, involving the posterior cingular cortex, medial prefrontal cortex and medial temporal lobe, which are all involved in creating stories in your mind, and disconnecting from outside distraction. While there have been

But ballet is not typically something you only do by yourself. In fact, one of the most beautiful things about ballet is when the corps the ballet moves in perfect synchrony, such as the entry of the shades in La Bayadere. To make this happen, dancers need to be highly aware of the dancers that are in front of them, to the side, and behind them. In fact, they are even told to breathe together. As such, I would strongly suspect that not only their bodies synchronize, but even their brains synchronize (here is a video where I talk about inter-brain synchrony in dancers.

A final unique aspect of ballet is the extreme balance expertise required, Women even balance on the tips of their toes! Recent research has shown that dancers are better at balancing than non-dancers (Burzynska et al., 2017). Such balancing expertise was associated with changes in dancers' hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus (thought to be crucial for orientation in space), insula (thought to be important for feeling sensations inside your body)Dordevic et al., 2018).

|

| Brain areas larger in ballet dancers than in controls (from Dordevic et al., 2018) |

In summary, dance, and in particular ballet, is great for lots of things. Indeed, I found that in the last few weeks, when I was stuck at home due to the covid-19 situation, ballet was really my outlet and saving grace. The good news is that dance in general, and ballet in specific is nowadays also used in interventions for diseases such as Parkinsons (read more here). It has also been found that people who have been dancing their whole life tend to suffer less from dementia and age-related cognitive decline (Verghese et al., 2003). So, keep dancing!

No comments:

Post a Comment